On View

Not on viewObject number1999.17

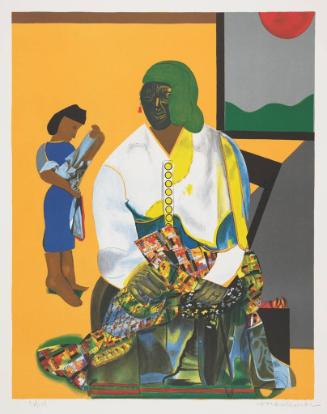

I'll be a Monkey's Uncle

Artist

Kara Walker

(American, 1969-)

Date1996

Mediumscreenprint

Dimensionssheet: 39 5/8 in. × 35 in. (100.6 × 88.9 cm)

framed: 47 1/2 × 42 1/2 × 1 1/4 in. (120.7 × 108 × 3.2 cm)

framed: 47 1/2 × 42 1/2 × 1 1/4 in. (120.7 × 108 × 3.2 cm)

Credit LineGift of Helen Sheridan in memory of Ben Tibbs

Exhibition History"Large Format Works on Paper," KIA (July 22 - Sept. 27, 1999).

"Energy and Inspiration: African American Art from the Permanent Collection," KIA Long Gallery (Jan. 13 - Apr. 14, 2006).

"A Curator's Legacy: Helen Sheridan and the KIA Collection," KIA Long Gallery (Dec. 20, 2008 - Apr. 19, 2009).

"Embracing Diverse Voices: African-American Art in the Collection of the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts," KIA Galleries 3&4(Oct. 3 - Nov. 29, 2009).

"Embracing Diverse Voices: 80 Years of African-American Art," KIA Traveling Exhibition, Bakersfield Museum of Art (Dec. 13, 2012 – Mar. 10, 2013).

"Lasting Legacy: A Collection for Kalamazoo," Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, Kalamazoo, Michigan (Sep. 6, 2014 - Jan. 4, 2015).

"Embracing Diverse Voices: 90 Years of African-American Art," KIA Traveling Exhibition, Tyler Museum of Art, Tyler, TX (January 17 - March 20, 2016).

"Embracing Diverse Voices: A Century of African-American Art," KIA Traveling Exhibition, North Carolina Central University Art Museum (October 7 - December 12, 2016).

"Africa, Imagined: Reflections on Modern and Contemporary Art," KIA Gallerys 3 & 4 (January 22 - May 1, 2022)Label TextThis screenprint features a barefoot, African American girl holding a dripping cloth. A squat, presumably male figure with a large head, flat nose, and long monkey tail faces her. The monkey figure and the title refer to the racist 19th-century practice of comparing African Americans’ physical characteristics and behavior to those of monkeys.

Kara Walker’s black and white silhouettes have been called lewd and grotesque, but also powerful and historically significant. Drawing her imagery from pre-Civil War narratives and African American stereotypes, Walker explores our perception of the “other.” Mimicking the 19th-century silhouette technique (also called poor man’s portraiture), Walker places her characters in a world where everyone is “black,” everyone is “other.” At first glance, her works have a humor and sarcasm that brings an initial giggle from the viewer, but the laughter fades as the viewer looks more closely and comprehends the messages of race, gender, and class.