On View

Not on viewObject number1960/1.108

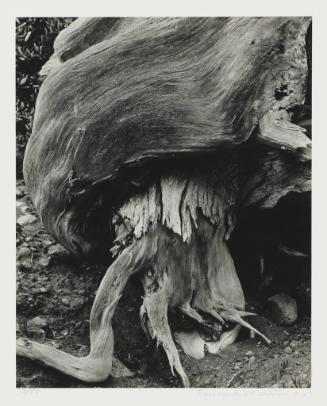

The Steely Barb of Infinity: #13

Artist

Minor White

(American, 1908-1976)

Date1960

Mediumgelatin silver print

Dimensionsmat: 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm)

mount: 18 × 15 in. (45.7 × 38.1 cm)

image (flush): 7 5/8 × 7 1/8 in. (19.4 × 18.1 cm)

mount: 18 × 15 in. (45.7 × 38.1 cm)

image (flush): 7 5/8 × 7 1/8 in. (19.4 × 18.1 cm)

Credit LineDirector's Fund

Exhibition History"Twentieth Century American Art: Painting, Drawing, Sculpture, Photography," KIA (Oct. 1 - Dec. 31, 1961).

"The Thing Itself: Daguerreotype to Digital," Dennos Museum Center (Dec. 6, 2003 - March 7, 2004).

"Abstraction in Landscape," KIA Second floor (Feb. - Dec. 2008).

"Light Works: Photographs from the Collection," KIA Long Gallery (Sept. 18 - Dec. 12, 2010).

"Light Works: A Century of Photography," KIA traveling exhibit. Nassau County Museum of Art, (Nov. 19, 2016 - Mar. 5, 2017).Label TextBorn in Minneapolis, Minnesota on July 9, 1908, Minor White is known for striking black-and-white photographs that captured people, places, and land. Throughout his career, White used photography to explore spirituality and the meaning of life. Together with Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams, White founded the renowned photography magazine, Aperture. He taught extensively at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco and later at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After his death on June 24, 1976, his photographic archives went to Princeton University. White’s photographs are not only a part of the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts’ collection but also in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. White’s grandfather was an amateur photographer. His grandfather’s encouragement during childhood led White to study botany at the University of Minnesota. There, in his photomicrography classes, White learned to develop and print photographs. Those magnified studies of nature profoundly influenced the artist’s practice. Said White, “A lot of times people would show various strange forms in art, modern art...and I’d say, I’ve seen all that under a microscope...” After graduating, White channeled his creativity into poetry, eventually moving to Portland, Oregon where his passion for photography reignited. There, he joined the Oregon Camera Club and refined his developing and printing techniques. White became a Works Progress Administration (WPA) photographer, which brought him to eastern Oregon in 1940. He immersed himself in reading about “the philosophy of photography, Edward Weson, and the F/64 school.” White’s approach to photography has been called philosophical — even mystical. He believed that image-making was a profound act that could provide an opportunity to commune with the universe. White had a unique perspective about a photograph’s ability to provide a bridge between the sacred and the profane. This realization drove much of his photography and teachings. His images are steeped in introspection, somberness, and a quiet solitude, presumably in an effort to discard worldly desire. His careful abstractions invite scrutiny. Said the artist, “At first glance, a photograph can inform us. At second glance it can reach us.” This image, The Steely Barb of Infinity: #13, 1960, comes from a series mostly taken in upstate New York. This particular image, taken in Rochester, shows a snow-covered window and ledge. Another glance at the photo recalls the image of a pitchfork. This optical illusion, of what is seen versus what may be perceived, is what appealed most to the artist — that a photograph can change based on closer examination. The title of the work, The Steely Barb of Infinity, perhaps references a quote by the French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, whom White possibly viewed as a kindred spirit. Both Baudelaire and White had a keen interest in modernism and the impermanence of life. White felt responsible for capturing these experiences through his artistic practice. Thus, the series of photographs can be viewed as a meditation on the trials of life and man’s ability to withstand or succumb to them, while finding meaning in the ordinary. [Collection Highlight]