On View

Not on viewObject number1977/8.5

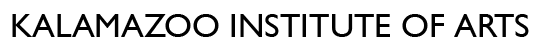

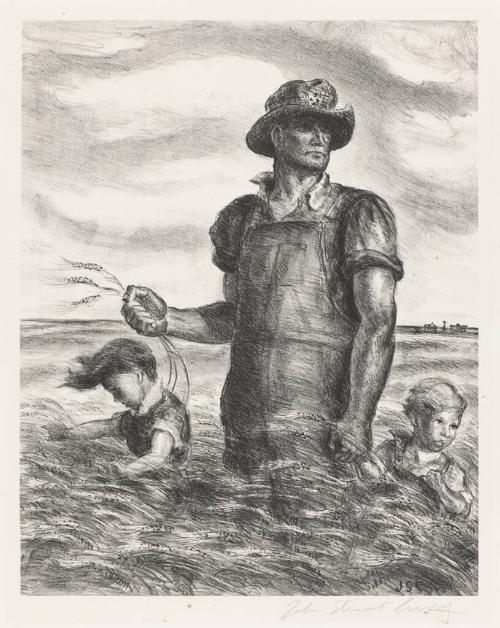

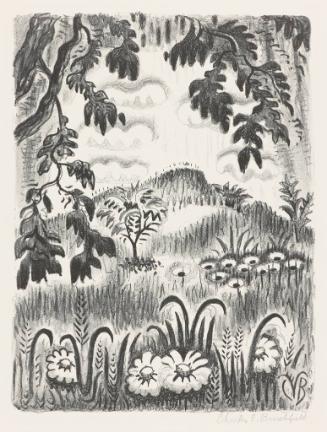

Our Good Earth

Artist

John Steuart Curry

(American, 1897 - 1946)

Date1942

Mediumlithograph

Dimensionssheet: 12 3/4 × 10 1/8 in. (32.4 × 25.7 cm)

image: 12 3/4 × 10 1/8 in. (32.4 × 25.7 cm)

sheet: 16 7/8 × 12 7/16 in. (42.9 × 31.6 cm)

image: 12 3/4 × 10 1/8 in. (32.4 × 25.7 cm)

sheet: 16 7/8 × 12 7/16 in. (42.9 × 31.6 cm)

Credit LineBequest of Mrs. Cornelia Robinson

Exhibition History"36 Regionalist prints from the KIA," Dennos Museum Center (Sept. 8 - Nov. 24, 1996), Ella Sharp Museum, Jackson, MI (May 17 - July 13, 1997), Midland Center for the Arts (Aug. 2 - Sept. 21, 1997).

"The American Experience: Prints and Drawings, 1900-1946," KIA Long Gallery (2002).

"A Curator's Legacy: Helen Sheridan and the KIA Collection," KIA Long Gallery (Dec. 20, 2008 - Apr. 19, 2009).Label TextRaised on a farm in northeastern Kansas and trained in Kansas City and Chicago, Curry studied in Europe before returning home to devote himself to representing Midwestern rural life. Our Good Earth, a heroic depiction of a farmer standing in a field of ripe wheat with his two children, is an expression of what Curry loved most about life in the United States. The image originated with a federal government request that Curry fashion a propaganda poster at the dawn of the Second World War. On the poster this scene was accompanied by the fear-inspiring words “Our Good Earth …Keep It Ours – BUY WAR BONDS”. Though largely a positive representation of the resilience and industriousness of American farmers at a moment when their efforts were sorely needed to support the war effort, the inclusion of the two children and the farmer’s anxious gaze into the distance imply concern for the future.

At the time he made Our Good Earth Curry was an artist-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin. Scholars have argued that he used this position to try to promote ideals that celebrated farm life and encouraged unschooled rural citizens to become more involved in politics and artmaking. This was part of an approach in which, like other Regionalist artists, Curry celebrated the rural Midwest as quintessentially American and promoted amateurism as a corrective to the supposed monopoly on creativity held by the sophisticated urban art worlds of cities like New York. This approach led Curry to be celebrated by some conservative critics in the 1930s and ’40s, but in more recent years has led scholars to decry his celebration of white farmers as the quintessence of American identity as racist and investigate his possible interest in eugenic thinking.