On View

Not on viewObject number2011.93

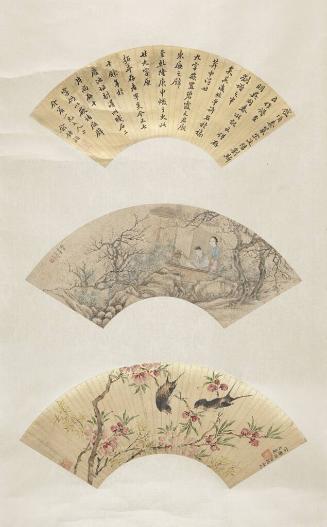

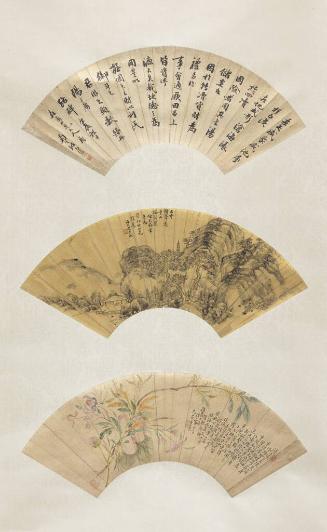

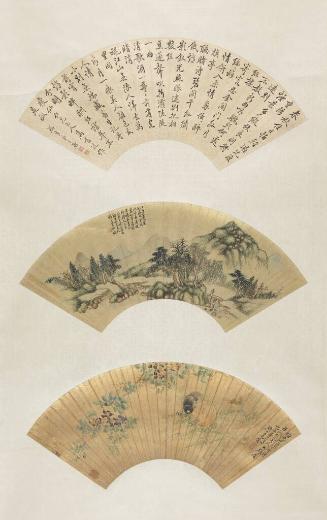

Bird and Flowering Rose

Artist

Zhu Cheng

(Chinese, 1826-1899 or 1900)

Daten.d.

Mediumink and color on silk

Dimensionsimage: 9 3/4 in. × 10 in. (24.8 × 25.4 cm)

mat: 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm)

mat: 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm)

Credit LineGift of Albert and Betty Chang, retirees of Upjohn Company and Kalamazoo Valley Community College

Exhibition History"The Chinese Scholar's Brush: Works from the Albert and Betty Chang Collection," KIA Joy Light Gallery of Asian Art (May 7 - Aug. 27, 2011).

"Copley to Kentridge: What's New in the Collection?," KIA (Sept.14 - Dec. 1, 2013).

"Rhythmic Vitality: Six Princliples of Chinese Painting," KIA Joy Light Gallery of Asian Art (December 9, 2017 - March 25, 2018)Label TextThe beauty for which Zhu Cheng’s painted fans were highly prized 120-150 years ago can still be readily appreciated today. Beyond their decorative appeal, these “bird-and-flower” paintings affirmed a connection to Chinese traditions during a period of political and cultural upheaval. Much of this painting’s beauty lies in a pleasing tension between circular movement and balanced calm. The arcs of several stems curve in harmony with the round silk, shaped to mount on a fan. A large blossom and small bird balance the view. This deceptively simple image demonstrates the artist’s skillful execution of compositional traditions. Densely painted foliage balances the equally important unpainted space. The linear stems are adeptly arranged to stimulate the eye’s continuous movement, without crossing the circular frame or appearing unnatural. Keen observation of nature was essential to mastery of bird-and-flower painting. The tiny brown bird bears the features of a warbler, known in parts of China for its sweet song in springtime. Thorny stems, a distinctive bud, and razor-edged mature foliage contrasting with the reddish hue of tender, unfurling leaves accurately depict a rose. Though less commonly featured in Chinese art than the peony, the rose was also a traditional symbol of spring. A successful work was to be both decorative and symbolic. The artist reveals the fleeting nature of life in the moment before a bird flits away and a fading petal falls. Yet, a new bud promises continued life and beauty. Shanghai experienced rapid change and growth during the 19th century, with pressures from civil strife on land and exposure to foreign influence by sea. As a result of the Opium Wars, China was forced to open the port city of Shanghai to foreign powers bringing Western ideas, culture, and commerce. From the southern countryside, rebel forces challenging ancient Chinese religious and social values caused disturbances that drove 100,000 people-including Zhu Cheng and many artists-to the relative safety of Shanghai between 1860-63. In the city, Zhu Cheng studied with two influential masters, synthesizing Zhang Xiong’s traditional compositions and techniques with Wang Li’s lively brushwork and vibrant color, which together defined the distinctive Shanghai style. Bird-and-flower painting was already a 700-year-old painting tradition in the 19th century. Viewers understood these objects of beauty as expressions of Buddhist and Taoist philosophies that the divine exists everywhere, in the harmony of man and nature, animals and plants. Thus, works like Zhu Cheng’s immensely popular bird-and-flower paintings connected the people of Shanghai to China’s ancient cultural heritage during a time of turmoil. [Collection Highlight]